Transit Scheduling 101: Scheduling Math ➗✖️

Frequency, runtime, layover, cycle time, and how they all relate to determine how much transit service costs to operate in this installment of Transit Scheduling 101!

Transit scheduling is a web of jargon and a handful of key formulas laying on top of an intuitive, but infinitely complex process. In this article, we’ll introduce some of the key terms and mathematical concepts required to understand the mechanics of transit scheduling. Fortunately, many of the terms should be pretty familiar (and division is the most complicated math we’ll be dealing with.1 Let’s get into it!

🗝️Key Terms

We’ll get started with a term that should be very familiar by now; frequency

Frequency (n) - The elapsed time between consecutive buses (or trains, or ferries) on a transit line. Put simply, how often the bus comes.

We’ve previously discussed the importance of frequency for providing transit service that is broadly useful to as many people as possible. Frequency has particular significance to transit scheduling, because it is one of the key drivers for how many buses and drivers are required to operate a transit service.

Runtime (n) - The time required for the transit vehicle to travel from one end of the line to the other.

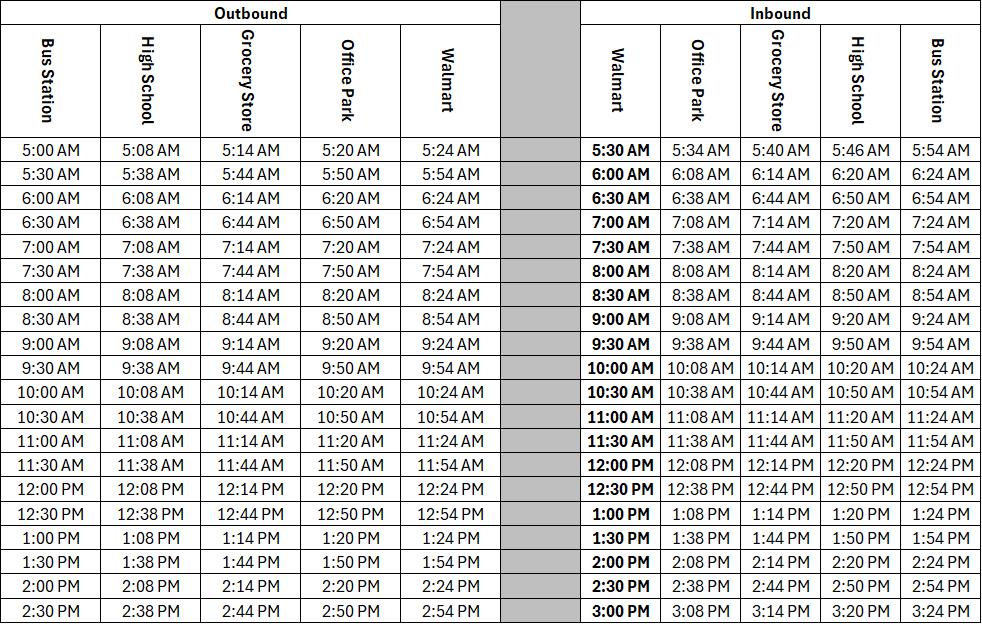

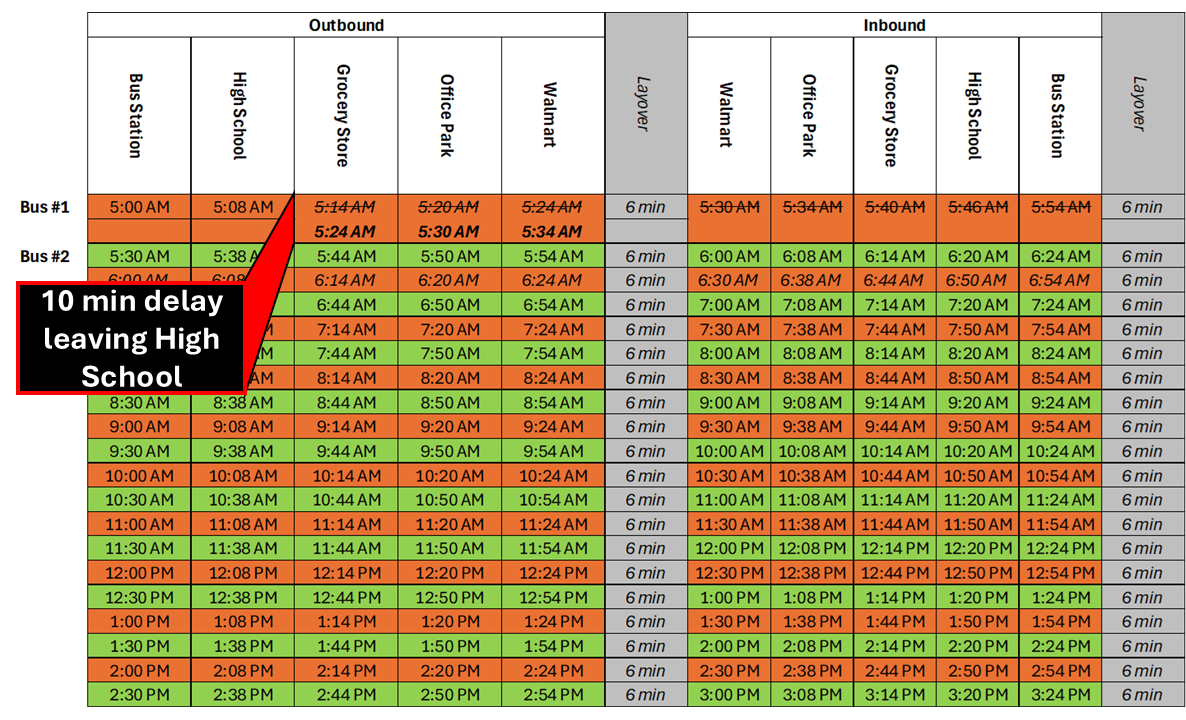

Runtime can be expressed as the one way runtime, or the round trip runtime, depending on the the structure of the route. Let’s revisit the schedule from the first series in this installment.

From this schedule, we can determine that the route has an outbound runtime of 24 minutes, and and inbound runtime of 24 minutes, giving this route a round trip runtime of 48 minutes.

This 48 minute, round trip runtime represents the amount of time it would take the bus to complete an outbound trip, followed immediately by an inbound trip, assuming nothing happens along the way and the route kept perfectly to schedule.

Maybe traffic was was particularly heavy this trip. Maybe the bus got stuck in the school pickup line. Maybe nobody had their fare ready, so boarding took longer than anticipated2. Maybe there were shenanigans afoot.

In reality, the bus is going to encounter some delay along the line. Even if the bus does keep to schedule, maybe the driver needs a break before launching straight into the next trip. To accommodate all of this, we have layover.

Layover (n). Transit Planning - Time scheduled into a transit route for the vehicle to recover any time lost in the last lap and start the next lap on time. This also offers an opportunity for the driver to take a break to prepare the best version of themselves for the next trip. At least 15% of the runtime is my minimum layover recommendation.

When life strikes, layover ensures that a delay incurred in the morning isn’t still wreaking havoc as the day goes on.

Assuming a minimum layover percentage of 15%, how much layover does the route from earlier, with a round trip runtime of 48 minutes require?

Layover = Layover Percentage * Runtime = 15% * 48 min = 7.2 min →8 min(Rounding up errs on the side of reliability)

Let’s continue with the same schedule and watch layover in action. Today, there was a special event at the school. The National Honor Society is taking a field trip to D.C. and everybody’s dropping off their kids. The 5am trip on Bus #1 got stuck in the fray, and as a result, is now running 10 minutes late.

Note that it has 12 minutes of layover (25%) per round trip, well beyond the 8 minute minimum. We’ll come back to why that is in a bit

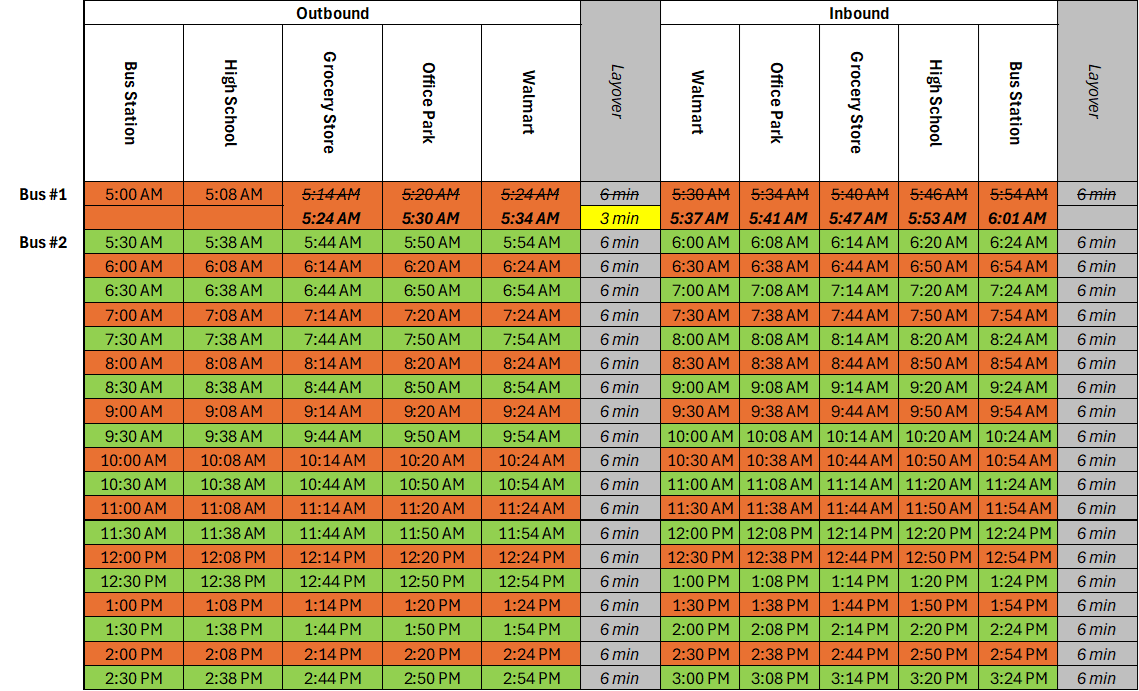

Because of this delay, bus #1 arrived at Walmart at 5:34, four minutes past when it was due to depart. The driver still is still owed some time to prepare for the next trip, but they didn’t want/need the whole 6 minutes of layover. After 3 minutes, Bus #1 departs Walmart at 5:37, now only 7 minutes behind schedule.

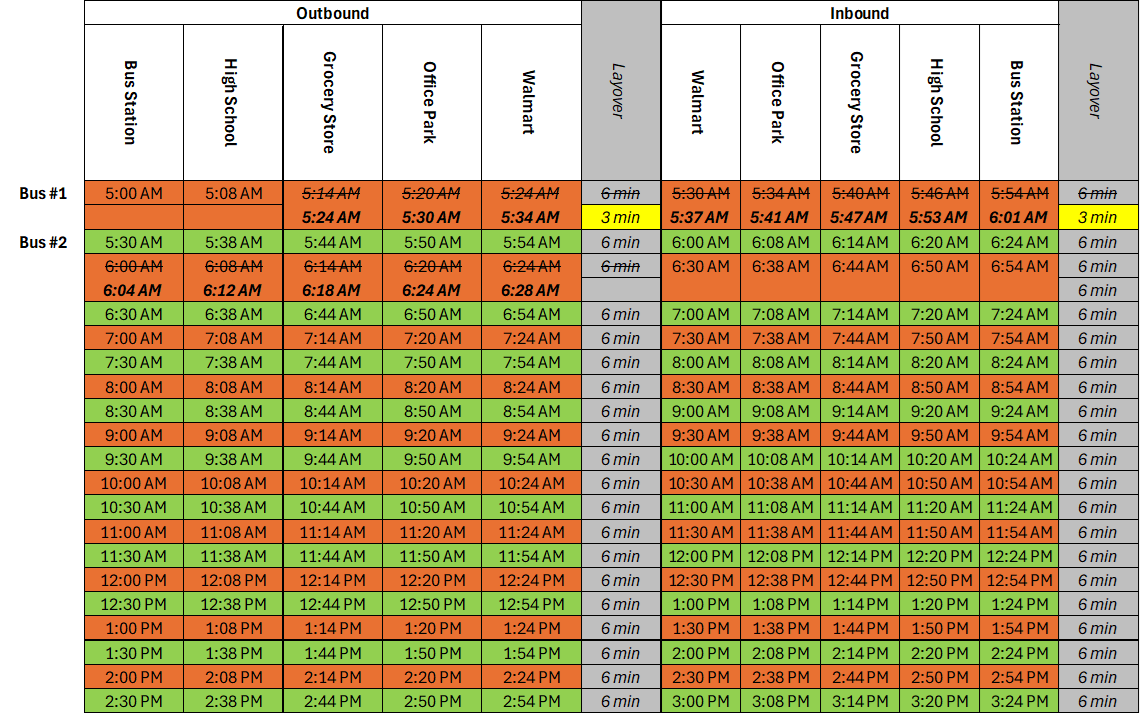

Bus #1 arrives at the bus station at 6:01, one minute past when it was due to depart. The driver takes another quick layover, and departs at 6:04, four minutes past the scheduled departure.

For many transit authorities, Bus #1 is technically on-time since it’s less than 5 minutes late.3

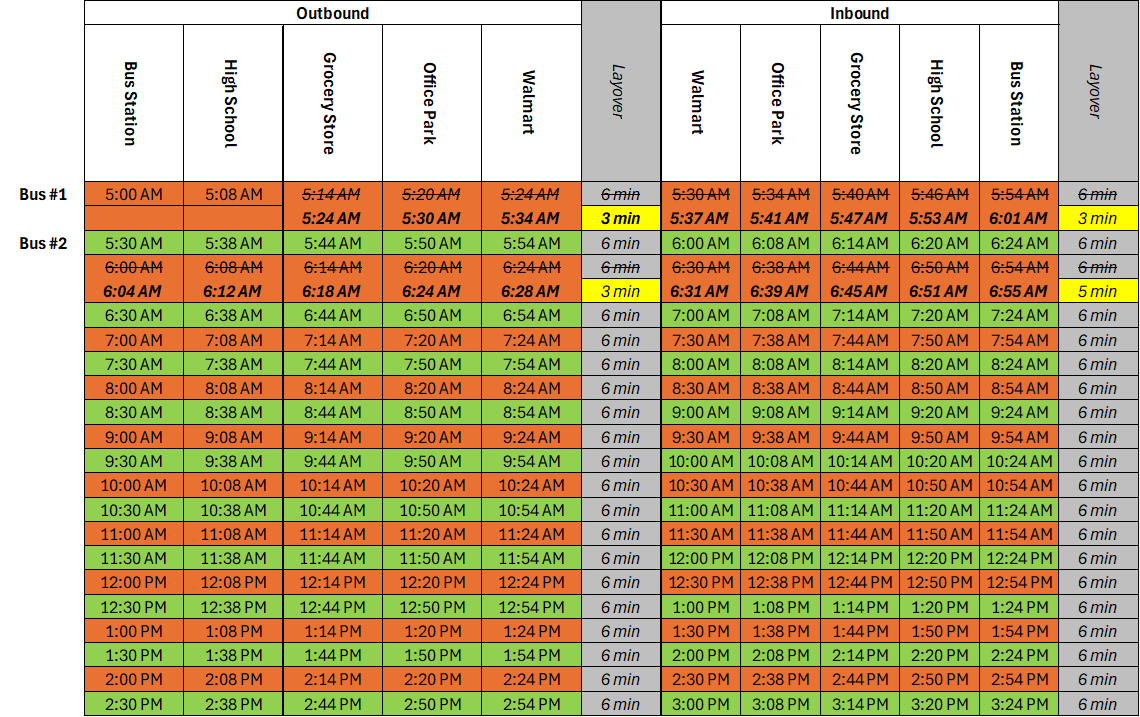

Bus #1 arrives at Walmart at 6:28, two minutes before it’s due to depart. I’m driving bus #1, and I’m sick of being late, so I take another quick layover and get the bus out of Walmart by 6:31, one minute past when I was due to depart. By the time I arrive back at the bus station, I’m basically on time, and get 5 minutes to relax my forehead before starting the 7:00 am trip on time.

Layover delivers the reliability required of Good Transit. If you’re still curious about why our route had 12 minutes of layover instead of the minimum required 8 minutes, you’re ready to learn about cycle times!

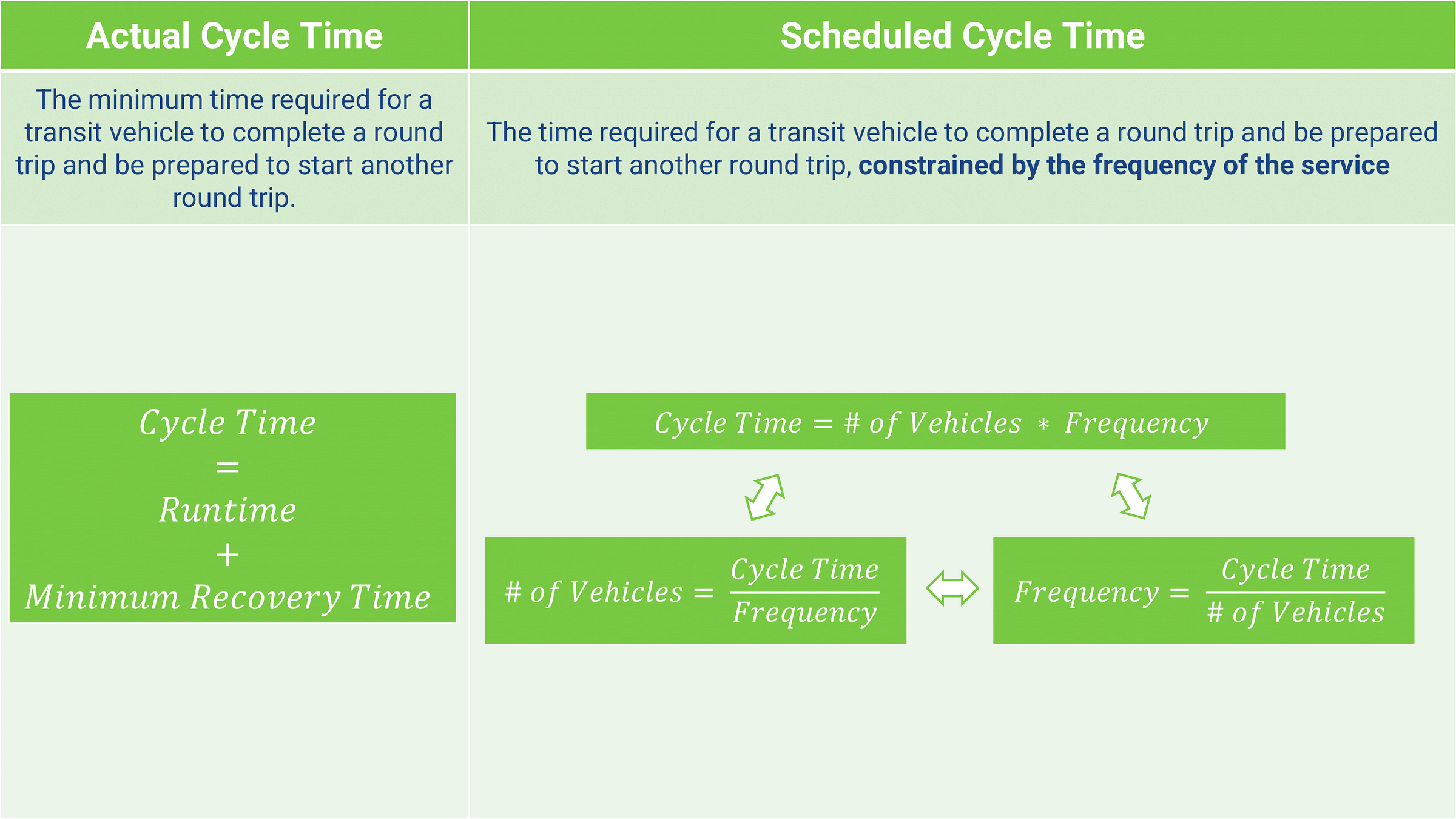

Cycle Time (n) - The time required for a transit vehicle to complete a round trip and be prepared to start another round trip, inclusive of layover.

The actual cycle time is the round trip runtime, plus the minimum layover required. For the route we’ve been working with, the actual cycle time is 56 minutes.

Actual Cycle Time = Runtime + minimum layover = 48 min + 8 min = 56 min

The actual cycle time is helpful for understanding the absolute minimum amount of time required to run a route. However, scheduled cycle time, informed by the route’s frequency is what drives the number of vehicles required to operate the service, which drives the cost of transit service overall.

Returning to the same schedule, we know that our route has an actual cycle time of 56 minutes, and a frequency of every 30 minutes. How many vehicles are required to operate the route?

Vehicles = Cycle Time / Frequency = 56/30 = 1.87 vehicles1.87 vehicle → 2 vehicles

With our new vehicle count, what’s our scheduled cycle time?

Scheduled Cycle Time = Vehicles * Frequency = 2 buses * 30 minutes = 60 minutes

The four minute difference between the actual cycle time (56 min), and the scheduled cycle time (60 min) is where we found the extra layover time, pushing the effective layover above the 8 min minimum, to 12 minutes, or 6 minutes per one way trip. Now that we have all of the tools, let’s do some scheduling math! If math’s not your jam, that’s totally fine! Skip the exercises and hop back in, in our next installment, where we’ll take what we’ve learned so far and actually build a schedule!

Scheduling Math ✖️➗

Here are some sample exercises putting the keywords and formulas we covered in this article into practice.

If your route has a cycle time of 120 minutes, and you have 4 buses available, how frequently can you operate this route?

Frequency = Cycle Time / Vehicles = 120 min / 4 buses =30 minIf your route has a cycle time of 120 min, and you only have 2 buses available, how frequently can you operate this route?

Frequency = Cycle Time / Vehicles = 120 min / 2 buses =60 minIf the cycle time of your route is reduced to 100 minutes, but you still only have 2 buses, how frequently can you operate this route?

Frequency = Cycle Time / Vehicles = 100 min / 2 buses =50 minHow many vehicles do you need to operate a route with a 60 minute cycle time, every 30 minutes?

Vehicles = Cycle Time / Frequency = 60 min / 30 min =2 busesHow many vehicles do you need to operate a route with a 60 minute cycle time, every 15 min?

Vehicles = Cycle Time / Frequency = 60 min / 15 min=4 busesIf you want your route to operate every 30 min, and you only have 1 bus available, how long can the maximum cycle time for this route be?

Cycle Time = Vehicles * Frequency = 1 bus * 30 min =30 minChallenge: How long can the round trip runtime be for the above route, assuming a 15% layover percentage?

Actual Cycle Time = Runtime * 1.15 ←→Runtime = Cycle Time / 1.15 = 30 min / 1.15 ≈26 min

📚 Buy me a Book 💚

Thanks for reading! If you enjoy my writing and want to support it in a small but meaningful way, consider buying me a book from my Bookshop.org wishlist. It’s the books that I want to read, but have not quite pulled the trigger yet!

I promise I wont judge you for using a calculator

To me, this is one of the stronger argument for fare free transit (or at least off-board fare payment). Paying fare slows the bus down, and often precludes operational improvements like all-door boarding. Plus, most disputes between bus drivers and passengers are fare-disputes.

It’s a much bigger deal if a bus is early, than late. Imagine you got to the bus stop on time, and the bus came 2 minutes ago.

Love the clarity here on how cycle time math directly ties to service costs. The layover section is especially underappreciated because most riders dunno that buffer time is what keeps morning delays from cascading into afternoon chaos. I used to consult on operational efficiency for mid-sized systems and the hardest sell was always convincing leadership that adding 10% more layover could reduce overall delays by 30%. The math works but it feels counterintuitive until operators actually see reliability improve.